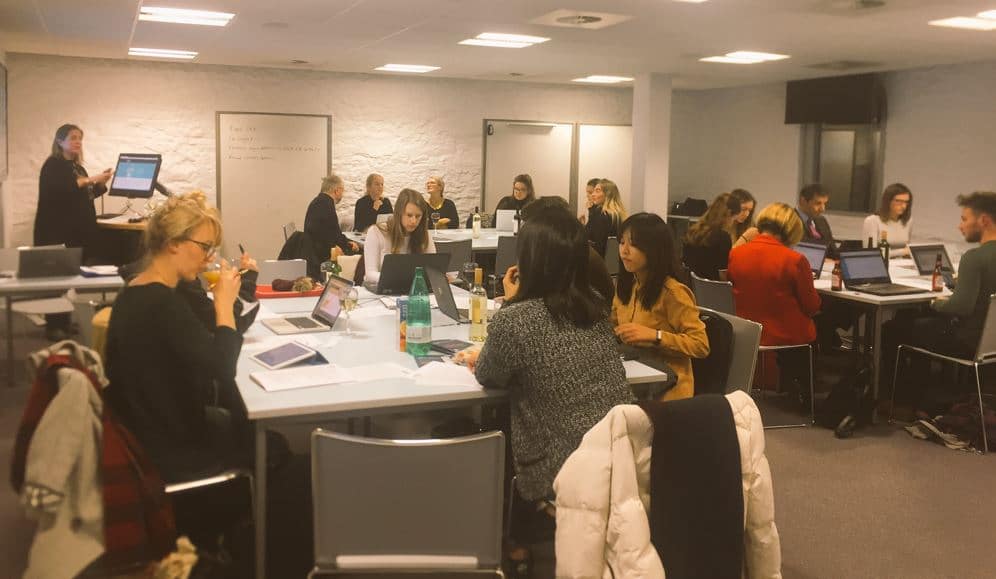

We’ve run a series of crisis simulations for the PRCA over the past two weeks (London 27 November, Edinburgh 28 November, Manchester 29 November and Bristol on 30 November). They were great fun for us to run, and attracted some really talented people -with a wide range of experience – senior PR professionals, students, lecturers and apprentices – who started many interesting and thought-provoking discussions.

There were some very similar themes across them all, and everyone wanted to continue the feedback discussions after we’d run out of time, so I thought it would be useful to document some of the discussions here. I won’t say too much about the storyline, as we’re running the workshop in Belfast on 25 January, other than it revolved around a rogue team member of a fictional music/tech company.

We're getting ready to start the @Polpeo crisis simulation here in Manchester with the fantastic @PRCA_UK pic.twitter.com/W8QMnCBZM3

— Tamara Littleton (@tlittleton) November 24, 2016

Rapid response versus careful consideration

Early discussions among all teams focused on when to respond. Most teams opted not to respond publicly to the escalating issue initially. Instead, choosing to observe who was posting, and what influence they had on social media.

Broadcasting a holding statement to Twitter, or your own social media channels too early in the crisis can amplify the issue, creating a much larger crisis for the brand.

The key lies in knowing at what point you should respond. For example, a utility company should know what ‘normal’ looks like on social channels – how many complaints or questions around billing or ethics are normal. When something changes significantly, that could constitute an escalating issue that needs a response.

It comes back to understanding what a crisis looks like for your brand. Is the action of a rogue employee going to materially impact the reputation of your business, or damage revenue, or the valuation of the company? If the answer is no, then it’s not a crisis, however much of a pain it might be to manage. If the answer is yes, then it’s a full-scale crisis.

Focus on owned or public social channels?

Monitoring your own channels is as important as monitoring public channels. You might discover an issue breaking on your own Facebook page, for example, that you can contain before it hits public channels.

Most of the teams across all the simulations (with one or two exceptions) put a much heavier emphasis on responding to people on public channels (Twitter in particular) than on their own channels (like Facebook). This interested me. In discussions, some teams felt that managing the issue on a public channel such as Twitter was more important than responding to questions on the brand’s Facebook page as it was more likely to escalate and reach a wider audience.

While this makes sense, the teams who did manage questions and comments on their owned channels fared better with the public over the full course of the crisis, as their customers felt that their voice was being heard, and so were more likely to defend the brand. Often we find that advocates are just as important as critics during a crisis, but sometimes these people are forgotten.

Develop a social media strategy

Other teams ignored social media in favour of responding to journalists.

I think this is probably a natural instinct in PR – to start the crisis by drafting a press statement (in some cases, well before the issue had attracted media interest), rather than responding to public questions on social media. While a statement is important, of course, that’s not where your crisis is likely to start.

A well thought out strategy for social media is every bit as important as your media approach. It’s easier to absorb the information in a tweet, or a Facebook post than to read a corporate statement, and during a crisis, people want information – not pure reassurance. Brief, transparent, communication can often bolster the impact of a good press statement.

Respond to (some) people on social

Whether to post personal replies or whether to broadcast statements to a wide audience also provoked discussion. Some teams felt that replying to people on Twitter would escalate the crisis as their friends would see the response, so effectively marketing it to a wider audience. Others felt that by replying directly to people, they would feel more valued.

Neither is wrong – it entirely depends on the crisis – and probably the best course of action is somewhere in the middle, responding to people with specific questions (rather than those who are simply directing abuse at the brand) and posting to all followers once the crisis has reached a level that it requires a public response.

Developing a good tone of voice

The thing I think most teams struggled with is tone of voice. It’s very easy to retreat behind corporate speak in a crisis – responding, but not really saying anything – and I don’t know what that adds, other than an acknowledgement of the issue. A statement that says: “There has been an incident and we’re looking into it” just piques interest and raises more questions. If your company values are ‘open, transparent, honest, refreshing’ (for example), a statement like this jars.

If you don’t know more than that, say “We’re hearing reports of X and while we don’t know more at the moment, we’ll let you know as soon a we do”. It sounds less as though you’re covering something up, and more appropriate for social media. If you have a crisis manual, practise adapting some of your initial holding statements to sound more open. It’ll engender trust, which will help you through the crisis.

Should you ever use diversion tactics?

This was a fascinating debate in all the simulations. Without giving too much away about the crisis scenario, there was an incident involving a company member, during an award ceremony that the company was putting on to showcase new musical talent. Should the brand shut down posts promoting the award? Or ignore the crisis completely so as not to take the focus away from the musicians that were the focus of the evening? Should it attempt to divert from the crisis?

As ever, the answer lies somewhere in the middle. I’m not in favour of diversion tactics, but shutting down all other activity in this situation probably isn’t realistic – it would be pretty hard on the young musicians up for an award if the company’s crisis took away all publicity from them. The show must go on.

Those teams who scored highly here clearly articulated their strategy, acknowledging the issue, but saying they didn’t want to take focus away from the musicians, so would continue to promote the event.

Taking business action

The teams had to make some quick business decisions. Will firing an employee help the reputation of the company, or make it look weak? Could the crisis have been avoided with a stronger business strategy that could be implemented to avoid it happening again?

A crisis team must have access to strong leaders in the business who can make difficult decisions, and who can approve action quickly. Communications on its own won’t solve the crisis.

When to delete posts

Deleting posts on your owned channels was also the cause of some debate. Some teams deleted every post that was overly negative, others deleted nothing to maintain the company’s value of openness.

Again, this is a balance. You don’t want illegal activity showing on your page, for example, or posts that are outright abusive. But you shouldn’t delete critical posts just because you don’t like them, or they don’t reflect your brand values.

Not only will they pop up again as quickly as you can delete them, but it’s a tactic that’s likely to enrage some fans, who could then go on to post their critical comments on social channels that the brand doesn’t control – spreading the crisis and alienating them from the brand. Whatever you decide, make it clear on your page what your policy is.

If you attended the event and have feedback for us on how it went and what you learned, or whether you agree or disagree with the points raised here, we’d love to hear from you.

–

Featured image credit — @SouhaKhairallah